Glass Without the Machines: A Meditation on Trust, Art, and Disintegration

One Fan's Reflections on the 25th Anniversary of The Smashing Pumpkins album: MACHINA

Preamble: Off-Topic, On-Pulse

This article is a departure.

It’s not about workforce modelling, patient flow, or governance frameworks. It won’t examine system resilience, audit trails, or regulatory metrics. Instead, it’s about music—specifically, a record released twenty-five years ago by a band that once fractured under its own weight, and the recent decision by its front-man to “celebrate” that record without the people who made it matter.

At first glance, this might appear extremely off-topic for a series rooted in healthcare leadership. But the deeper I reflect, the more certain I become that this is not entirely a detour - but it is a case study. Because this story, though draped in guitars and mythology, is really about continuity, rupture, authorship, and trust—the very things healthcare lives and dies on.

If you’ve ever stood by a team through crisis, through recovery, through reinvention—only to see that team disbanded or rebranded without ceremony—you may recognise the ache that follows. If you’ve ever built something hard, together, and watched it be repackaged as someone else’s vision or project, you’ll know why this is not about nostalgia. It’s about meaning.

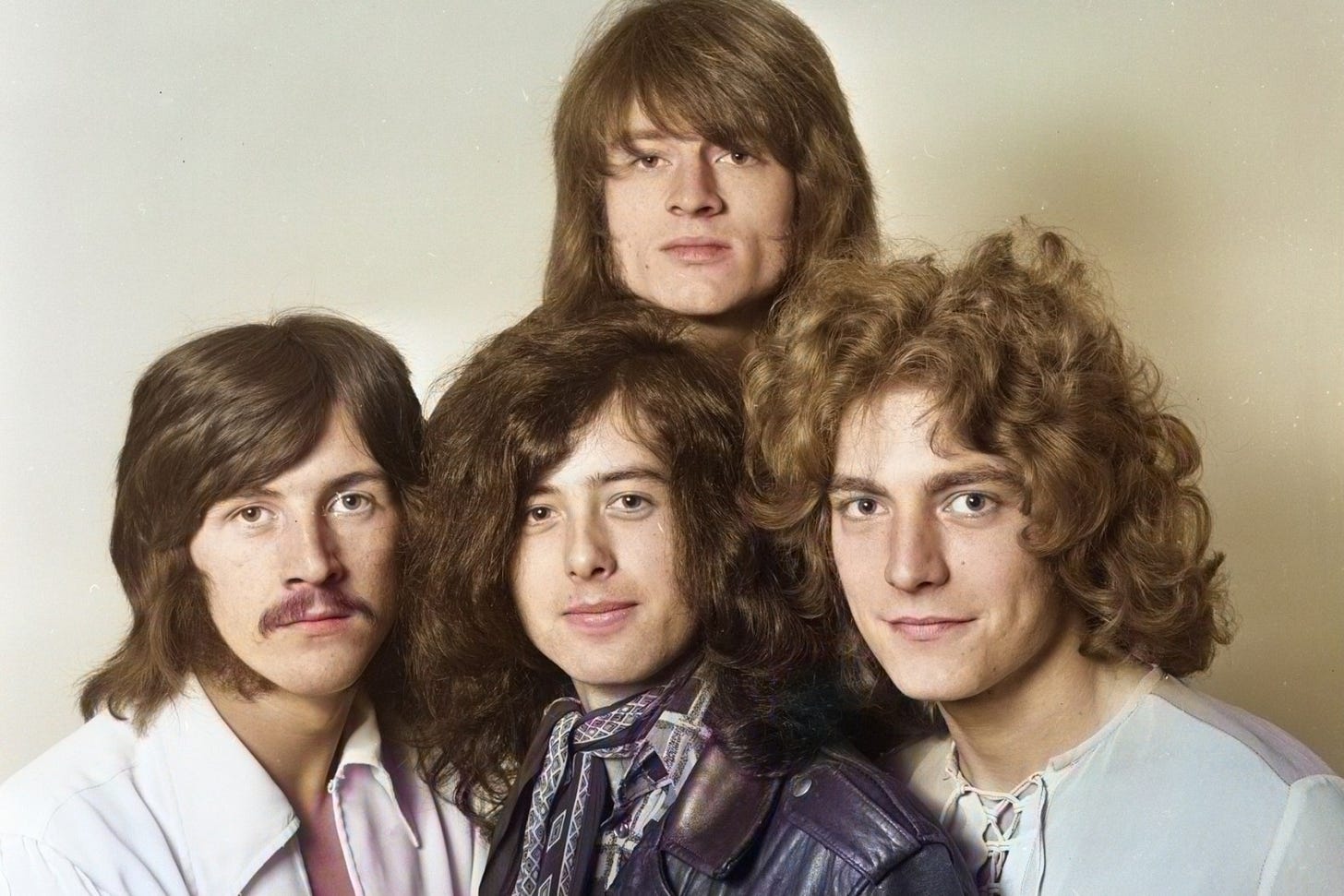

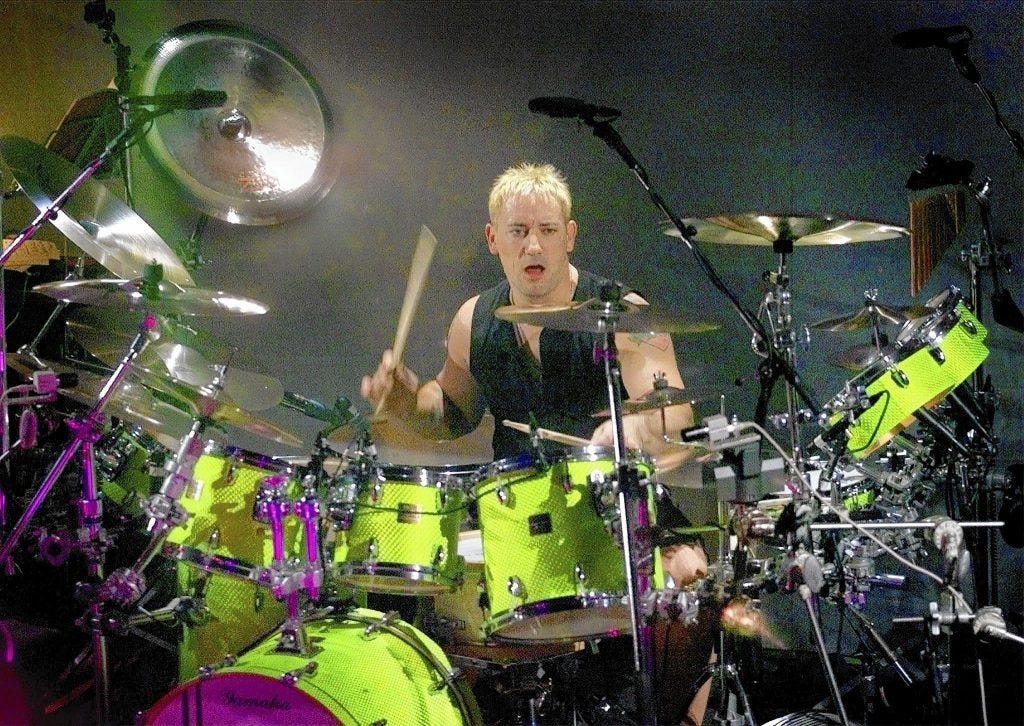

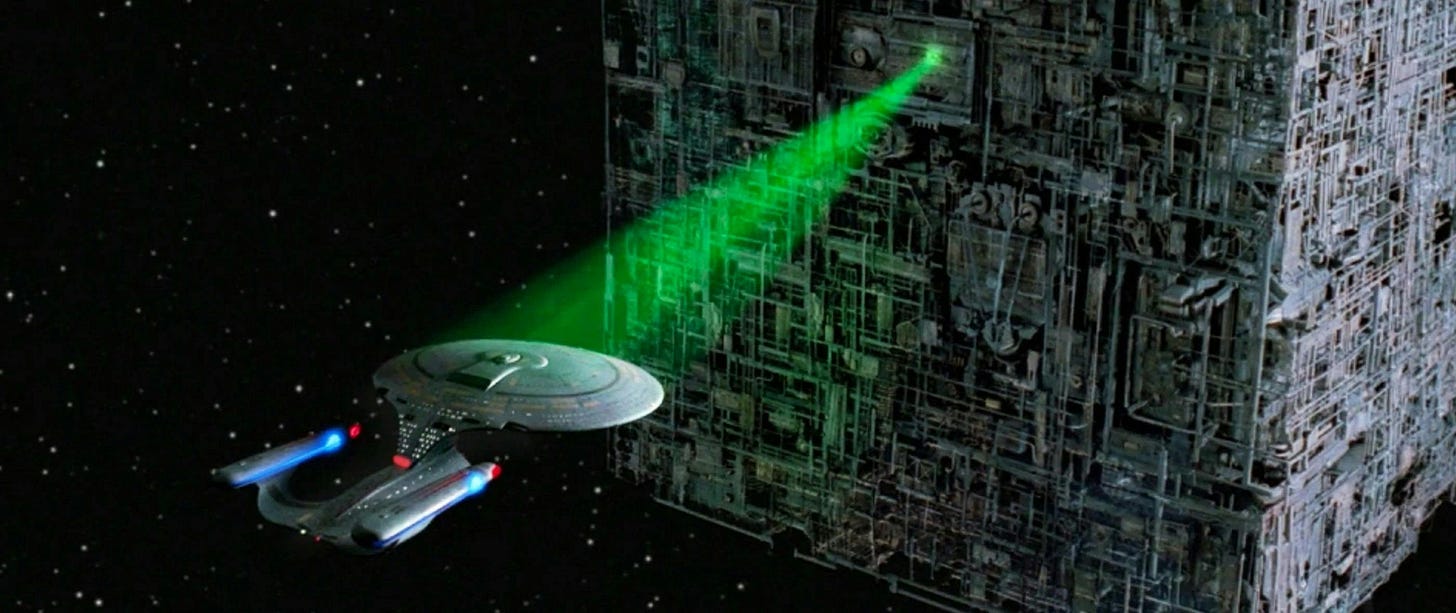

Machina/The Machines of God is, on the surface, a rock album by The Smashing Pumpkins. But underneath, it is something stranger: a liturgical concept record about ego, prophecy, and the disintegration of spiritual community. It is also the album that marked drummer Jimmy Chamberlin’s return to the band—a moment that, to some of us, felt like resurrection. Not of a brand, but of a relationship.

This piece will not seek to dismantle joy.

If the form of the current “revival” brings joy to others, that joy is valid. But this article is written from the position of someone who once felt seen by a band that, to me, was more than one man’s vision—and who now finds that vision redrawn without the very people who made it luminous.

In healthcare, we say continuity of care is sacred. This is a story about continuity of art—and what happens when it is broken.

If you wish, you can listen to an “AI” summary of the article right here. (There are a couple of errors / or glitches but it does an OK job at covering most things)

Prologue – A Need to Speak, Not to Persuade

This is not about nostalgia.

It’s not a demand for a reunion, nor a claim to ownership, nor an insistence that things must remain as they were or to be different. It’s something quieter, stranger, and more difficult to articulate: an attempt to make sense of a shifting myth—one that I once felt part of, and now find myself watching from the outside.

I’ve been thinking about this all week… since the announcement… but in truth, I’ve been living inside the questions since 2000. Back then, I was part of the conversation. Not passively as now — presently. I was there in the fan forums of the late 1990s. I burned the bootlegs. I deciphered the lyrics. I traded tapes and theories, formed friendships, went to the shows, talked in person, listened to every podcast, every outtake, every argument.

My view is not the view. But it is a view formed not in isolation, but in the long, strange communion that this band once inspired.

What follows is not a critique.It is something else… A musing. That is all.

Because something is happening now — a reframing of Machina, of The Smashing Pumpkins, of memory itself—that I can’t just absorb in silence. All I can say is, that it would feel like a betrayal of the younger version of me to let these emergent emotions go unspoken.

A new tour has been announced. A new vision presented. And while it seemingly brings joy to many, and while I honour that joy, I also feel a fracture. Not musically—spiritually. What once felt like a shared act of myth-making now feels narrowed, as though some of the audience which was once part of the narrative has been moved from the centre to the edge - to behind the curtain…

And I don’t write down any of this to change that. I write it because if I don’t, my own memory of what Machina meant—what it was—will begin to evaporate into silence.

And silence, when something once mattered this much, feels like a second loss.

I’m not claiming that my view is definitive. Far from it. But it is true—to me. It is rooted in lived experience, in emotional investment, in twenty-five years of bearing witness. And I believe there is value in naming one’s perception clearly, especially when history is being reassembled in real time.

So this is not a plea for restoration. It is a (*cough*) record of dissonance. It is a meditation on continuity, authorship, trust, and the haunting feeling that something once sacred is being reshaped without the people who gave it form and resonance.

It may be that the myth was always more fragile than I believed. It may be that the fracture I feel is not betrayal, but evolution. And if so, I will learn to let it be.

But before I let it go, I want to mark its passing. I want to say, aloud and with clarity: this is how it felt to witness the myth, to live inside it and out - and to watch it change. This is my trace. Not a correction. A footprint.

I don’t pertain to know what’s really happening behind the scenes. I don’t presume insight into the personal dynamics, decisions, or intentions that have shaped this new chapter. My reading is shaped—as all readings are—by my own personal lens. As a drummer. A bandmate. A songwriter. An art historian. A father. A healthcare manager. A fan. And an anonymous presence on the internet who, for better or worse, thinks too much and feels deeply. I may have it all wrong. But perspective isn’t about being right—it’s about being present. And right now, this is how it feels. I wish I could feel the unfiltered joy that others seem to. I don’t. Something has happened. Something has been reframed. And in that shift, something beautiful feels, to me, partially lost—shattered in a way that invites not outrage, but mourning. This is not a lamentation for the past.

It’s a reckoning with what it means when the myth no longer recognises your place within it.

Introduction – What We Hold, and What We’re Asked to Let Go

There are albums you like. There are albums you revisit. And then there are albums that—whether you understood it at the time or not - helped to knit parts of you together —Machina/The Machines of God was that for me.

Released in 2000, it arrived at a strange and liminal moment: the original lineup of The Smashing Pumpkins was fracturing, public sentiment was waning, and yet this record sounded unlike anything else—grandiose, messy, mystical. It was a transmission from a band on the brink, and something about its scale, its ambition, and its vulnerability made it feel less like a release and more like a reckoning. It wasn’t perfect. That’s what made it feel “True”.

But what made it real—what gave it weight beyond concept—was the return of Jimmy Chamberlin. After years of estrangement, his presence didn’t just bring back the band’s engine; it recalibrated their spiritual centre. The energy surrounding the Arising! tour in 1999 wasn’t just nostalgia. It was resurrection. This wasn’t about replaying old glories. It was about forging something stranger, darker, and more daring than before. Chamberlin didn’t just rejoin—he allowed them to transcend.

To my teenage self, this mattered. Not just as music, but as proof that forgiveness, repair, and creativity could co-exist. The Smashing Pumpkins, fractured and fallible, were still a band, a collective ideal, worth believing in — not because they were functioning smoothly, but because they were trying to make meaning in the wreckage.

Machina, for all its cryptic references and unpolished edges, felt like a dispatch from inside that struggle. It didn’t ask to be liked. It asked to be witnessed.

So when I see that same album—along with Mellon Collie and Aghori Mhori Mei—being “revived” or “celebrated" under the banner Billy Corgan and the Machines of God, with a new touring band and no James Iha or Jimmy Chamberlin, something fractures again. Not musically—technically, it will likely be proficient — but relationally. Spiritually. Symbolically. The souls who made that first resurrection possible aren’t just absent. They’re totally unacknowledged.

Please, let me be clear. This isn’t a rejection of those who are excited about the new tour or Corgan’s vision. If this version brings you and him joy, I honor that as best I can. Music doesn’t belong to any one interpretation. Corgan—who shaped the songs, the story, the scaffolding—has every right to attempt to reclaim and reinterpret his own work. He has always seen further than most of us. He may well believe that what I and others saw in that period in 1988-2000 and then again from 2018-2025 was illusory—fan fiction, projection, longing for a unity and importance of the band, The Smashing Pumpkins, that never existed. And if that’s the real truth, so be it.

But at that time, particularly in 1999-2000 something else was real to me and thousands and thousands of others. It was real to many of us who grew up between Gish and Machina, who didn’t just follow the band’s sound but felt shaped by its internal dynamics—the tension, the collapse, the rare moments of grace and humour. Of course they were just glimpses, but we hung on every word. Maybe it was the Millennial Doom that hung laden in air - is there was a small chance the world would really end at the strike of midnight…

We watched, the band back then, those moments not as consumers but as participants in a shared story. And if we hold those moments dearly, it’s not because we think they belong to us, but because they once included us.

This is not a critique in bitterness. It is an elegy in sincerity. I am not writing this to argue that a new version of Machina is illegitimate. I write because I once believed that resurrection, when it came again, would include the people who made the first fall survivable. And what we are being offered now—however sonically faithful it might try and be — is, to my mind, a hollow celebration of an album born from repatriation.

Billy Corgan can rightly claim authorship. But Machina was never just direction—it was collision. And without the particular individuals who helped shape it—especially a drummer widely considered among the greatest in the genre—it becomes something else. Perhaps still powerful. Perhaps still moving. But no longer what it was.

That doesn’t make this proposed tour meaningless. But it means, for me, I can’t celebrate it without mourning what has been set aside.

Zero Revisited: A Myth Re-framed Without Its Makers

On 29 March 2025, Billy Corgan announced a new North American tour under the name Billy Corgan and the Machines of God. The tour, titled A Return to Zero, represents the most symbolically loaded live undertaking since the Smashing Pumpkins' reformation in 2018. But this is not a Smashing Pumpkins tour. It is curated, led, and performed under Corgan’s name—framed as both a return and a reframing. An intentional design to evoke the past…

According the new press release, the setlist will draw from three albums:

Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995),

Machina/The Machines of God and Machina II/The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music (2000)

Aghori Mhori Mei (2024)

Conspicuously absent from the live framework is ATUM — a 33-track, three-act rock opera released between 2022 and 2023, that was explicitly billed by Corgan as the final chapter of a narrative trilogy beginning with MCIS and Machina. ATUM continued the story of Glass and built on the spiritual collapse at the heart of Machina.

It was an epic, if uneven, effort at thematic closure.

And yet, the first curiosity - ATUM—the binding agent—is omitted from the live show. Instead, A Return to Zero leaps past it and returns to the earlier texts, re-presenting them not in full, but as selected fragments—curated by Corgan, sequenced by him, and performed without the members who once gave those albums their visceral grounding.

This reframing coincided with the long-anticipated release of the Machina box set—a monumental 80-track collection that finally unites Machina I and II into the double album originally intended (*we shall come back to this) in 1999–2000. Remixed, remastered, and sequenced into a coherent whole, it is Corgan’s attempt to complete the unfinished cathedral of his career’s most spiritually ambitious work.

But unlike Gaudí’s Sagrada Família—whose vision, interrupted by death and resumed by disciples, remained faithful to the architectural language of its creator—The “celebratory tour” A Return to Zero completes the vision without the disciples. There is no James Iha. No Jimmy Chamberlin.

Their original contributions are not explicitly denied, but they are not conspicuous by their absence. The press release contains no mention of their absence. There are no statements from either party.

This absence is not just logistical. It is structural. Corgan may be attempting to finish the cathedral alone, but the stained glass—cut, fired, and placed by others—is missing from its windows.

Machina itself was born from disintegration. Chamberlin had just returned after his departure in 1996. Iha was distant. D’arcy left. The songs were dense, erratic, brilliant. The release was compromised. The myth was fragmented. But the spiritual centre of the record—the tension between prophecy and collapse—only worked because of the band’s unstable integrity. It wasn’t clean.

It was sacred because it was strained.

That sacred strand extended into CYR (2020), and ATUM (2022) and Aghori Mhori Mei (2024), which again features Chamberlin and Iha and were released under the Smashing Pumpkins name. It gave the impression—at least to many—that the band was functioning, fractured but real. Glass and The Machines had really returned at last. That the myth could only be completed with the people who survived it.

Now, this tour bypasses that sacred structure.

Machina is being performed not in full, but in parts. MCIS is revisited, but not through the lens of shared legacy. Aghori Mhori Mei is invoked, but ATUM, the supposed narrative fulcrum, is also gone.

This is not a trilogy completed. It is a retrospective curated by one of its authors. And for some, that distinction is profound.

The question, then, is not whether this will be musically strong. It likely will be. The question is what kind of relationship it asks the audience to accept. For those of us who believed that Machina was sacred not only for its sound, but for its context—for the pain and people who shaped it—the dissonance is deep.

This is not a collapse. But it is a reordering of meaning. And meaning, once reordered, cannot easily be reclaimed.

Authorship, Control, and the Need to Reclaim the Frame

To critique with integrity, one must first try to see with the artist’s eyes. Here I may fail spectacularly from my removed distance as a mere observer - but in earnest I will try. But I have no doubt that one counter to all this is; “you have completely misread every aspect of what Machina was really about” and therefore, this argument can be dismissed completely. But this is not an argument. Its an observation and you can’t argue that the observation hold -no- value, that isn’t how history works. Comments and aural histories of individuals do matter and do provide context… For my perception is valid as a response, as it is a reflection of a significant proportion of the [online] fan-base (at least)...

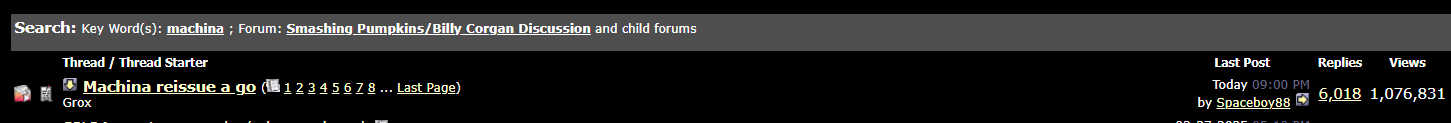

As an aside, it is possible that posts and perspectives such as this—critical, complex, and often dissenting—will once again be scrubbed from the official websites and media channels of the band, as they have been before. But there will remain voices and echoes elsewhere—on message boards like Netphoria.

Frequently misunderstood, sometimes marginalised, this long-standing fan forum is nevertheless home, for example, to some of the most dedicated curators of the Smashing Pumpkins’ live audio archives. Promoting the band even when the band disbanded. If these aren't loyal and true fans I don't know who are... And it is where fans have been selected for exclusive listening parties, or engagement with archival projects. Of course, some of these will have left a sour taste in the mouth of the band - they didn’t always pan out and it’s easy to shorthand critism to "the community” when really it was the failure of a few individuals.

Netphoria deserves closer attention. It does not speak with a singular voice. It doesn't like some other niche fan communities “like” everything the band does in equal measure.

Instead, it is a site of argument, divergence, and enduring debate. Its culture is hard to explain if one hasn’t lived it for the past 25+ years. Like the Machina mythos itself, the forum continues to evolve—defined not by consensus but by persistence. Many of its posters remain engaged simply because of their enduring connection to the music. And, naturally, some feel the music no longer meets their expectations.

Because those expectations are high—for good reason. When a fanbase believes this is the greatest band in the world, disappointment is not casual; it is ferocious. Vitriol is a byproduct of emotional investment. Whether those expectations are fair, correctly understood, or even possible to fulfil is a separate question. Who sets the terms? And what happens when they’re broken? The Machina reissue, for instance, was first mooted for release in 2013. It arrived 12 years later. In any other business or marketing context, this would be considered a catastrophic failure of delivery. So critism naturally follows…

On Netphoria, another recurring theme emerges: the belief that the biggest obstacle to the wider recognition of the Smashing Pumpkins as the best band in the world is, paradoxically, Billy Corgan himself. If even the most discerning fans cannot distinguish between Corgan the artist, the persona (“the heel”), and the person—then surely this is a problem for someone who has long expressed a desire to be understood, appreciated, and correctly interpreted.

Critics might call Netphorians gatekeepers. A more generous view would describe them as curators or stewards. After all, no other online fan community has persisted for this long. The forum even outlasted the band during its 2000–2007 hiatus, remaining active and engaged with solo releases and side projects.

This is not, nor can it be, a defence of every post or poster. Netphoria is a constellation of individuals, not a monolith. Some threads are comically hyperbolic, others deeply insightful others , are indeed crass. But taken together, it remains a rare example of unmoderated, fan-driven dialogue—a bastion of free expression in the world of the Smashing Pumpkins.

A dark band with a dark, sardonic edge is bound to attract fans who reflect that same sensibility. This should surprise no one.

The main point, however, is not about tone but about significance. Netphoria exists as a living artefact of sentiment. As evidence: a single thread—initiated in 2018 when the Machina reissue was first said to be legally cleared and in production for release —has now amassed over 6,000 posts and more than a million views. Seven years later, that thread is still active.

Dismiss this at your peril. It means something.

That aside

Billy Corgan is not just the frontman of The Smashing Pumpkins. He is its architect. Its archivist. Its animating force. From the earliest demos to 33-track concept albums, he has constructed a canon not always driven by market logic but by internal myth. Even his detractors concede this: he does not make music casually. His creative process is monastic. He speaks not in singles or eras, but in cycles, cosmologies, and spiritual fractures.

To that extent, Machina was not simply another record. It was his cathedral—a metaphysical system of prophecy, narrative identity, self-destruction, and transfiguration. Its failure, commercially and structurally, was not just disappointing—it was personally desecrating. The myth collapsed not just within the album’s storyline (Glass is abandoned by the Machines of God), but in its making. The band broke apart. The double album was rejected by the label. The visuals and animation were shelved. The fans were split between confusion and cultic devotion. To an artist obsessed with coherence, this must have been intolerable.

And so perhaps this tour is not, to Corgan, a disruption—but a kind of spiritual closure. Not just a concert, but a final authorship. A gesture that says: If no one else will finish the story, I will. And perhaps only by doing it under a new name—Billy Corgan and the Machines of God—can he shift the frame. Not to erase the band, but to suspend the historical weight of what The Smashing Pumpkins has come to mean. He is not recreating the band. He is reclaiming a myth.

The irony is that many fans feel the opposite: that the myth only existed because of the band. But for Corgan, that may be precisely the point of divergence. From his perspective, Machina was his—written, arranged, directed as his response to the circumstances of the time. He has spoken many times about how, by the end of the 1990s, the band was disintegrating around him. He recorded much of Adore alone. He carried Machina’s conceptual weight almost entirely himself. The others contributed, but the vision—what he might call the burden—was his alone.

This does not make him right. But it makes him human.

And there’s a deeper truth here too. Billy Corgan has always seemed haunted by what is unfinished. Machina is not the only open wound in the catalogue. There’s Zwan… arguably some of [his] best work goes unreleased and under appreciated. He doesn’t just release music—he tries to stitch ruptures. In that context, this tour is not a celebration of the past. It is a ritual of narrative repair.

But this repair, I suppose, he thinks can only be done on his terms. Because to revisit the past with the full band intact would also mean revisiting the dynamics that broke it. It would mean sharing the spotlight. It would mean confronting the real conditions under which Machina was made—the conflict, the fatigue, the private and painful depatures. And perhaps he doesn’t want that kind of healing. Perhaps this isn’t about healing at all. It’s about ownership.

The visual artist Anselm Kiefer offers a powerful parallel. Known for large-scale works about history, myth, and trauma, Kiefer often revisits finished paintings—layering new materials, sometimes burning them, sometimes burying them. For Kiefer, a painting is not finished until it has been lived in, until its meaning shifts with age. What emerges is often scarred, altered, reconstituted. It is not what the audience saw the first time. But it is truer to him.

Billy Corgan may see Machina the same way. Not as a museum piece to be preserved in full fidelity, but as a canvas still under revision. He has the original artwork. He has the vaults. He has the means. And now, he has distance. And with distance comes the urge not to restore, but to reinterpret.

Machina I + II as “Originally Intended”?

The idea that Machina I and II were always intended as a singular, coherent double album has been central to Billy Corgan’s narrative for years. And in a structural sense, it may well be true—lyrically, thematically, mythologically, the records are connected. But coherence in retrospect is not the same as coherence in creation.

Given the chaos surrounding the band at the time—the breakdown of relationships, the departure of D’arcy, the exhaustion is, the industry’s rejection of a double album—it’s difficult to believe that a clear, stable vision governed all the originally sequenced tracks, as they were released. Machina 1, with 15 tracks, and Machina 2, with 14. 29 tracks in total.

Corgan himself has acknowledged this: that Machina was fragmented not just by external forces, but internally too. The vision was there—but so was grief, disorientation, and collapse.

At the time of its release, Machina was framed by Corgan through a sprawling, self-authored mythology—Glass and the Machines of God—published in parts online and inprint and embedded within the album’s arc. In this narrative, Glass (Corgan’s alter ego) leads the Machines (a symbolic stand-in for the band: James, D’arcy, and Jimmy) in a doomed spiritual crusade through fame, faith, love, and madness. The Machines begin as divine instruments of transmission—electrified partners in vision—but are gradually lost to disillusionment, silence, and entropy. Their disappearance is woven into the myth itself: not as betrayal, but as fragmentation. What was once shared purpose becomes solitary authorship. This was not a hidden subtext—it was the official story, unfolding in real-time across tour diaries, cryptic chapters, and public broadcasts. The Machina myth, even then, was as much about the disintegration of the band as it was about the songs they left behind.

Large parts are thankfully and faithfully archived in glorious detail here:

So when we now receive a newly sequenced, 48-track version of Machina—remixed, reordered, and positioned as The intended form—we must ask: are these sonic and emotional choices truly what would have emerged in 1999–2000? Would this structure, this clarity, this emphasis, have existed in the moment of original rupture? Almost certainly not. For they did not.

But that doesn’t mean it will lack a new and different value. That isn’t what I’m saying or mounting an argument against. I am simply “recognising” the new transmutation…

In fact, the distance—the two-and-a-half decades of reflection, loss, change—might offer something exceptionally rare and quite novel in itself and will I hope be the real center of attention on its release. If Machina was the sound of a band unravelling while still trying to sing, then this box set may be the sound of that voice, finally—if incompletely—trying to understand itself.

Still, it’s important to recognise that this reconstruction is not just a restoration. It’s a revision. An editorial act. One that reshapes memory and mythology. It claims coherence where there was once dissonance. It imposes order on chaos. And while that may help some listeners access the material more easily, it may also obscure what made the original myth so compelling: its unresolved nature.

Because Machina, then and now, resists finality. Even polished, it remains misunderstood—perhaps even by design. It was never meant to be consumed simply. It was meant to be inhabited, struggled with, lived inside. And that fact remains true, even if reframed and repackaged.

Perhaps that’s the deeper truth Corgan is circling: that misunderstanding is not failure—it is fidelity. The true reflection of The Smashing Pumpkins has always been this tension between vision and reception, between myth and mess, between authorial control and communal confusion. The blurring of lines—between Billy and Glass, between band and avatar, between sincerity and performance—was not a flaw in the design. It was the design. And what a design…

And this is where I return, not to critique, but to awe.

Because despite the fractures, the interpersonal chaos, the dissonant mythologies—these songs still stand. Not as relics of a broken era, but as towering, multifaceted works that—if anything—surpass the scope of Mellon Collie in their emotional and spiritual ambition. There is something in Machina that defies easy assimilation. It isn’t designed to fit cleanly into the catalogue. It haunts the catalogue.

And central to that haunting is the very idea that the band were both themselves and their shadows. Real musicians. Real relationships. But also avatars—Glass and the Machines. The parallels were not fictional—they were documentary. This wasn’t cosplay. It was transfiguration and transmutation. The songs so clearly allegorically rooted in the “real” bands collapse and rebirth… This Time, for example… It is a sacred retelling of life and death and hope. Real and surreal.

So yes, the songs speak for themselves. But they also speak through something. Through tension. Through myth. Through fracture. And that’s what may make the expanded Machina not less -real-, but certainly more complicated. Which is genuine cause for celebration or at least… reflection.

It is not a window into the past. It’s a mirror held up to the present—showing us what was lost, what was reclaimed, and what can never be fully resolved.

In contrast to the recorded “restoration”, this “live” reinterpretation is not free from it’s own significant consequence. In choosing to do live shows as “Billy Corgan and The Machines of God” without James and Jimmy (the original eponymous Machines) —publicly, without context or seemingly invitation — Corgan has redrawn lines of authorship and ownership. And for him, perhaps, that feels honest. They were part of it, but they were not the whole of it. He may believe that the mythology came from him, the lyrics from him, the thematic intent from him. And in doing so, he may feel justified in re-performing the work on his own terms.

But it’s also likely he believes he is honouring the work. That he’s protecting it from becoming just another nostalgia show. That by stepping outside the “Smashing Pumpkins” brand, he can create something immersive, strange, and spiritually faithful—not to the band’s history, but to his inner vision.

This may be a pilgrimage, not a tour. For him, it may be the most honest thing he could do.

And for many, it will land. The songs will resonate. The live band will be exceptional. The visuals will carry weight. For those encountering Machina for the first time—or hearing forgotten pieces in a new light—this may even feel revelatory. The joy that emerges from those performances will be real, and no one should deny that.

But what follows in this musing is written not to challenge that joy, but to sit with another emotion: the feeling of estrangement from something once shared. The sense that a sacred collaboration has been reframed into a single-author project. And while that may be artistically valid, it does not come without loss.

This is not a challenge to Corgan’s genius. It is a recognition of it. But it is also a recognition that genius, when isolated, often forgets the cost of removing others from its frame.

The Clinical Analogy – The Consultant and the Disbanded Care Team

Imagine you’re a long-term patient—on dialysis, or undergoing regular infusions, or part of a community frailty pathway. You’ve been under the care of a particular consultant, but just as importantly, under the care of a specific team: nurses, physiotherapists, HCAs, administrators, even transport drivers and porters. The plan may be authored by one person, but it is delivered through dozens of hands, eyes, voices, and choices. It is not a monologue. It is a conversation that unfolds in time.

You begin to know their habits. They know yours. They remember that your daughter worries more than you do. They see the difference in your walk before you speak of pain. They notice when your silence isn’t serenity, but fear. This isn’t magic. It’s continuity—the accumulated trust built not through heroism, but through repetition, context, and presence.

Now imagine arriving one day to find the team is gone.

The consultant is still present. The care plan hasn’t changed. The documentation is complete. The system says nothing is wrong. But the people who understood your fear without you speaking it are no longer there. The new team is capable. Professional. Efficient. But they’re not the same. And so the treatment may continue, but something has been broken in the space between.

That something is not quantifiable—but it is real.

In NHS England’s 2023 Staff Survey, only 30.8% of staff said they felt their team worked effectively together across organisational boundaries. Continuity of care was cited by patients in the 2022 GP Patient Survey as one of the most important factors in feeling “cared for as a person, not a condition.” It’s not the protocol that instils trust—it’s the people who repeat it with presence. When those people are disbanded, the plan may remain intact—but the meaning it carried does not.

We see this most acutely in winter.

Every year, hospitals activate temporary escalation wards to manage seasonal pressure. Staff are redeployed, rotas are stretched, and new teams form almost overnight. And astonishingly, the care is often excellent. The humanity persists. But when spring comes and the ward is stood down, what disappears is not just a service. It is a team—a short-lived, high-functioning unit with its own relational texture. Its own unrepeatable rhythm.

And with that disbandment, something is lost.

What is lost is never written down. It’s in the patient who finally trusted a nurse enough to speak about their home situation. The Health Care Assistant who noticed a drop in appetite. The cleaner who offered levity at exactly the right moment. These aren’t inefficiencies. They’re care itself—woven not through documentation, but relational presence.

The same is true of bands. And albums.

A musician can write the part. Another can play it. But what made the original performance powerful wasn’t just the note—it was the relationship behind the note. Machina was not simply a set of songs. It was the sound of a band in collapse, trying to transcend itself. Chamberlin’s return gave it force, Corgan’s vision gave it shape—but James Iha’s presence gave it balance.

Indeed, Machina may be the most musically integrated of their albums since Siamese Dream, and Iha’s voice—so often subtle—is unusually pronounced. His restraint, his spacious phrasing, his tonal counterweight softened the record’s extremes. Where Zeitgeist later over-accelerated under Billy and Jimmy’s joint propulsion, Machina held its form because of Iha’s pull against the current. He wasn’t ancillary—he was essential. A kind of quiet centre amid chaos.

To perform those songs now with different players may yield technically perfect results. But something is missing. Something has been stood down. Not because the new musicians lack skill. But because what they replace was not technical—it was relational.

Just as even the most gifted consultants are powerless without diagnostics, nursing presence, procurement chains, estate support, and trust in the room—so too is a singular musician incomplete without the infrastructure that gave his vision weight.

A band, like a care team, is not a delivery system. It is the context through which meaning is made visible.

Corgan may still be the consultant. But the ward has changed. The team has changed. The structure has changed. And though the song may be the same on paper, what holds the patient—in this case, the audience—is not the paper. It’s the people.

Lore and Liturgy – Machina as Myth, Not Just Album

It wasn’t pretty. It was esoteric, imperfect, and deeply encoded.

It was, by any commercial standard, a failure.

But in that failure, something transcendent occurred.

The Story of Machina was present as “A Modern Fable” - in summary:

Glass (Corgan) is a prophet of the near future—once the world-famous Zero of The Smashing Pumpkins—who, upon hearing a divine voice on the radio, rechristens himself as Glass and his band (The Smashing Pumpkins, Chamberlin, Iha and Wretzsky) as The Machines of God. In a collapsing society of fractured souls and technological alienation, he becomes a messianic figure to the [Ghost Children], their fans, preaching love as salvation. But torn between his spiritual calling and his longing for June—his shadowed mirror—Glass spirals into delusion, ego, and loss. As his faith collapses and his love dies, he is abandoned by fans, haunted by doubt, and erased from public memory. Only in isolation does he find peace—not through divine validation, but in rediscovering his flawed humanity.

Stripped of promotional clarity and hobbled by internal collapse, Machina became not a product to be consumed, but a myth to be decoded. Websites sprang up dedicated to charting its storyline aside from the myriad of Official “mystery” websites, with clues revelaing snippets of songs and talking us to other webpages - all part of the “Machina Mystery”.

The online myth that was being constructed was cutting edge revolutionary. Fans mapped lyrics to characters. The visuals were dissected like scripture. The songs weren't linear—they were oracular. Half-messages from a band already falling apart.

On the most popular fan forums like Blamo, Netphoria, The Pumpkins.net, The O-board, the fans became active participants in decoding the mystery. The music was a starting point—not the endpoint. Lyrics weren’t just poetic fragments, they were confessions, transmissions, fractures in the myth’s surface. Machina II, released for free, wasn’t a supplement—it was the second book of a cryptic gospel. Fans didn’t just download tracks—they restored cover art, reconstructed sequences, interpreted naming schemes like chapters of Gnostic scripture.

We were not passive listeners. We were believers, archivists, interpreters. And Corgan, for all his distance, seemed to acknowledge this. When he entrusted Machina II to a handful of fans with 25 copies of the record —literally, physically, handing over [master copies] to let them to let us copy and share it — it was an act of trust so far ahead of its time that it still hasn’t been properly honoured in the cultural record.

Before Radiohead gave away In Rainbows, before Bandcamp, before social media artists crowdsourced distribution—Corgan decentralised the second half of his most spiritually significant work and handed it to the audience.

That was faith and truly revolutionary in the time.

This act deserves far more attention than it received and the Band and Corgan should rightly be hearalded with ushering in the era of alternative decentralisation

But faith, as with medicine, requires more than vision. It requires trust. And trust is not just about permission—it is about relationship. It means making something vulnerable, and allowing it to be received, not just managed. It means recognising the audience as co-custodians—not simply consumers.

And here’s where the cracks began.

Corgan has often spoken in interviews about how Machina was misunderstood. That fans didn’t receive it warmly. That it landed in silence, or confusion, or hostility. And yes—there was scepticism. The record was dense. The production was sonically challenging. Songs like “The Imploding Voice” felt alien to those who’d heard its rawer, earlier form as “Virex” on Arising tour bootlegs. The arrangements were layered, obtuse, mixed for drama rather than clarity.

For fans of the band, at the time, the first song they heard from Machina was Glass’ Theme, live. The song was obviously special to the band. Powerful. Visceral. The introduction to “Machina”. But it was absent from the official release of Machina 1. Equally Dross, the very next song played live - became perhaps a bigger fan favorite online - again, not present on the release. Nor was another favorite from the Arising, Crash Car Star - again, saved for Machina 2 as was Home… It seems obvious in retrospect that not including these on the record and replacing them with other songs, such as “The Crying Tree of Mercury” which is a sonic world apart - would create a fracture in the reception … Maybe the band had underestimated how liked those songs were, I don’t know?

But I do know, Machina the album, was never outright rejected by the fan community that I knew and have known. Really the opposite is true in many cases it was embraced like no other record has been since…

I remember going to my friend’s house after school, spending hours downloading bootlegs of those Arising shows. I remember the awe of hearing “Glass’ Theme,” “Cash Car Star,” “Blue Skies Bring Tears” in their primal form. We didn’t reject Machina. We lived inside it. We interpreted its shifting forms—its dissonance, its occluded beauty—as part of the myth. The same was occurring online.

If anything, one could point to a fracture coming not from the audience breaking trust—but from the system that elevated a few. Those early listening parties, the decision to give preview access to selected fans, inadvertently created a “gatekeeping” hierarchy. It wasn’t collective. It was tiered. Some were seen. Others were excluded. And in a mythos already about collapse and betrayal, that separation cut deep.

Yet despite all this, the album endured. It became, for many of us, a favourite. Not in spite of its strangeness—but because of it. Where Mellon Collie was cosmic, Machina was ruinous. Where Siamese Dream was angelic, Machina was industrial theology. Its brokenness felt prophetic.

And over time, one may argue it has become the most emotionally resonant record of the band’s career.

Jimmy Chamberlin and Corgan have both used that word resonance before, carefully and repeatedly, to describe what Machina tapped into. Not success. Not clarity. Not coherence. But resonance: a frequency that vibrates across time, often without being fully understood. Something that doesn’t just move sound waves—but moves people. Machina didn’t resonate because of polish. It resonated because of its instability. Because it left room for interpretation. Because it required faith (and faith can help you to escape…)

Glass was never autonomous. He was, as the myth told us, an empty vessel. A conduit. The band—the Machines of God—were his manifestation. But so were we. The audience. The fans - the Ghost Children. The decoding, the myth-building, the hours spent reconstructing narrative out of sonic debris—that was part of the liturgy. Glass needs the Machines, and the Machines need the Ghost Children

To remove any link from that chain is not merely to change the performance. It is to change the ontology of the work.

And yet that is what the new tour does. It reframes the myth not as a living ritual, but as authored material. The resonance becomes reproduction. The mystery becomes repertoire. The sacred instability becomes restaged control.

This is not inherently bad. But it is not Machina as we once knew and understood it.

Corgan may still believe he is telling the same story. But if Glass is now a solo figure, and the Machines are session players, and the believers are asked to receive rather than respond—then the triad has collapsed. Not entirely musically, but spiritually and allegorically. Artist, band, audience: each was a voice in the symphony. And now only one of those remains intact as it was.

This doesn’t invalidate what’s being offered. But it repositions it. What once echoed across mythologies—Christian, Hermetic, Gnostic, Egyptian—is now bounded by control. The ritual has become a recital. The chaos has been cured. And that, for many of us, feels like the one thing Machina was never meant to be.

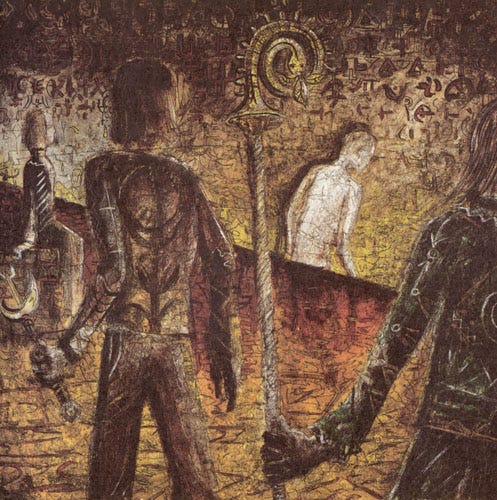

Visual Alchemy: The Art of Machina and Its Enduring Legacy

(Select images below from the album artwork, by Vasily Kafanov)

The visual identity of an album often serves as a portal into its sonic landscape, with iconic covers like The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band exemplifying the profound synergy between music and imagery. In the case of The Smashing Pumpkins' Machina/The Machines of God, Vasily Kafanov's artwork is not merely an accompaniment but an integral component of the album's narrative fabric. It formed a key part of the revolutionary online websites that accompanied the pre-release and release of the record. It was gorgeously layered across the booklets and inlays - it uniquely revealing other aspects of the Machina myth - expanding the narrative arc of music and lyrics to the visual realm. It was a multimedia cacophony. And again, essential to the music’s framing at that time.

Kafanov, a Russian-born painter renowned for his surreal and alchemical motifs, crafted a visual lexicon for Machina that delves into themes of transformation and mysticism. His illustrations, rich with esoteric symbols and dreamlike figures, encapsulate the album's exploration of the interplay between humanity and divinity, the organic and the mechanical. This collaboration resulted in a cohesive artistic vision that resonated deeply with fans and band members alike. Notably, drummer Jimmy Chamberlin valued Kafanov's contributions to such an extent that he acquired original pieces for his personal collection, underscoring the artwork's significance within the band's creative milieu.

The impending reissue of Machina, aiming to unify the narratives of Machina I and Machina II, introduces a complex challenge: how to reconcile and integrate the distinct artistic profiles of the two original releases. The decision to commission new artwork for this consolidated edition has sparked contemplation among the fanbase, especially given reports of a dispute involving the use of Kafanov's images on merchandise such as skateboards—a commercialization that some argue diminishes the original art's sanctity. This situation elicits empathy for Billy Corgan's protective stance over the album's visual representation.

However, the choice to engage a different artist for the reissue's visuals has been met with mixed reactions. For those who hold Kafanov's work as synonymous with the Machina experience, this shift presents a dissonance, challenging the long-standing synchronicity and resonance established over two decades. While the prospect of a "new and finally complete" edition is intriguing, the departure from Kafanov's established imagery raises questions about maintaining the original spirit and the band's historical connection with its audience.

In the broader context of album art history, where visuals like those of Sgt. Pepper's have become inseparable from their musical counterparts, the evolution of Machina's artwork underscores the delicate balance between artistic integrity, commercialization, and fan engagement. As the reissue approaches, it remains to be seen how this new visual interpretation will honor the legacy of Machina and resonate with both longstanding devotees and new listeners alike.

Jimmy and James – Not Session Players, but Co-Authors and Avatars

To suggest that Machina can be faithfully revisited without Jimmy Chamberlin and James Iha is not simply a practical misstep—it is a philosophical collapse. These weren’t players executing cues. They were shapers of resonance. Authors of tone. Avatars of intention.

To exclude them is to rewrite the grammar of the record—not just its personnel.

Jimmy Chamberlin – Translator of Myth into Motion

To a non-musician or non drummer, Chamberlin is a “great drummer.” But to those who know, he is a singular voice in the vocabulary of rhythm. His work is not just technically dazzling—it’s metaphysically structural. A prophet not of tempo, but of movement.

Billy may have built the cathedral of Machina, but Jimmy lit the incense and rang the bell.

As a drummer, you feel it in your bones. Chamberlin’s parts are not additive—they are formative. His ride cymbal doesn’t colour a section—it defines its geometry. His fills are bridges of meaning. He uses displacement, hemiolas, grace-note lattices, and explosive triplet figures not as display, but as dramaturgy.

In Glass and the Ghost Children, for example, the drums aren’t merely atmospheric—they’re hallucinatory architecture. Ghosted snares decay into silence while crashes hit off-beat like collapsing altars. He creates a psychological timeline within the song—shaping how the listener experiences internal collapse.

Glass and The Ghost Children - Live 29/11/2000

On Machina, Jimmy Chamberlin transcends the role of drummer; he becomes a co-author of the record’s architecture, its breath, its bones, its blood. Where earlier albums showcased his raw virtuosity—equal parts jazz precision and rock ferocity—Machina presents Chamberlin as a painter of time itself. His drums do not merely keep rhythm; they articulate subtext. They speak the unspeakable, filling the psychic gaps between Corgan’s cryptic lyrics and the dense guitar palimpsests with something primal, fluid, and ineffably human.

This is not a case of a great drummer accompanying a songwriter. It is an interdependent alchemy: Chamberlin’s ghost notes mirror Corgan’s emotional hesitations; his cymbal washes swell and recede like ocean tides around the vocal phrasing. Chamberlin becomes the medium through which chaos is ritualised into order—not restrained, but rendered sacred. His touch is paradoxical: thunderous yet whisper-thin, elusive yet anchoring.

Geek U.S.A from the Arising Tour (10 April 1999)

Just like D’arcy said here, no other drummer alive could have served Machina’s complex spiritual and sonic ambitions. The snares crack like apocalyptic scripture, then vanish into triplet hi-hats and jazz-inflected syncopations. There is a sense of drumming through the guitar rather than behind it—matching the tonal saturation, responding in realtime to the looped decay and synthetic flourishes. It’s a feat of neural synchrony. Chamberlin’s intuition is so exacting it feels algorithmic, yet it never loses its soul. He is, quite literally, composing with skin and wood and metal the very soul of the Machines of God.

Even in the album’s most chaotic moments he resists predictability yet retains distinction. His patterns refuse grid logic, instead opting for narrative. Listen closely and you will hear phrases, sentences, not just beats. Cymbals aren’t ornaments but choral symbols. Kicks land not on the one, but on the why.

To speak of Machina without acknowledging Chamberlin’s presence is to mishear the work. Corgan may have drawn the mythic structure, but Chamberlin etched its breath. The pairing on Machina isn’t performer and accompanist—it’s quantum entanglement. Drums and guitar. Flesh and filament. Ghost and machine. No clearer than in “Heavy Metal Machine” where Chamberlin’s drums sing with the same clarity as Corgan. This is a band on the edge of disintegration - press rolling harder and faster into glorious controlled chaos… The audience here, The Ghost Children, directly invited by the Machines to participate in the performance clapping and signing in union by the band…

Heavy Metal Machine - Live 29/11/2000

Goosebumps.

Every. Single. Time.

And yet, Chamberlin can go from the sonic labyrinth of Glass and the Ghost Children to Wound, where a thunderous tom-led groove doesn’t just arrive—it heralds the apocalypse. But this is not heavy-handed aggression. It’s flow state made manifest. The toms don’t bludgeon—they envelop. The groove is tectonic, yes, but it also breathes. It surges forward with controlled velocity, never tipping into chaos, always driving the narrative home. This is not metal. It’s something more refined—ritualistic. His dynamics are compositional. He’s not playing a part. He’s shaping the trajectory of a psychic event.

His genius is not excess. It’s navigation. He knows when to speak in tongues and when to whisper.

Adore, beautiful in parts as is, but it reveals what’s missing without him. Even with programmatic elegance, it lacks the breath of the living and complete band. The percussion becomes metaphorical. Atmosphere replaces intention. It is not necessarily [worse]. But it is most certainly other.

And Machina was the act of returning the breath.

Corgan said in interviews that when Jimmy returned, it felt like coming home. He didn’t mean it sentimentally. He meant the body of the band could move again. And so Machina became a liturgy not only of collapse, but of resurrection.

The fact that this current tour revisits Machina without him is not merely revisionist. It is conceptually incoherent. Because Machina was never written for a metronome. It was written for Jimmy. His ghost notes, his dark ride cymbals, his sense of gravitational time—these were not garnish. They were gospel.

Without him, the songs might still be “played.” But they will not breathe.

This is Chamberlin’s identity and if you want to hear a little more, listen to him speak about expressing that identity a little more clearly than I…

“No one will ever remember the guy[s] who play like Buddy Rich, Dave Weckl… Vinnie [Colaiuta]… or Tony Williams… when you can listen to those guys…”

James Iha – The Harmonic Ghost in the Machine

Iha’s voice is quieter, but no less vital. It is harmonic counterpoint—not accompaniment. His playing occupies the emotional perimeter, colouring the negative space with psychic tension.

It’s in the subtle chords left unresolved, the EBow harmonics that haunt rather than clarify and the the quiet delay trails that sit nested abstract under the vocal harmonic. These are brushstrokes on an icon.

Iha is not ornamental. He is restraining gravity.

Zeitgeist—for all its force—is what Machina might have become without James. The tonal spectrum narrows. The emotional dissonance flattens. The weight becomes constant. That’s not a dig—it’s an observation. Zeitgeist burns bright but does not flicker. It doesn’t breathe in the same way because the tensional foil is gone between the two leading Guitars of Corgan and Iha.

Machina breathes because Iha is there to restrain. He gives shape to silence. He gives grace to the distortion. And that’s not passive work. That’s discipline. It’s knowing when not to play. It’s the long game. The unsung mastery.

This is why the return of James and Jimmy to the band in 2018 mattered so much, again... It wasn’t nostalgia. It was restoration. Corgan’s vision only truly sings when counterbalanced by those who understand how to ground his fire in structure.

To now perform Machina without them is if not entirely a betrayal, but it is most certainly a reduction. And that reduction echoes precisely the themes Machina warned against: self-idolatry, disconnection, spiritual control.

Because Machina was never about purity of authorship. It was about the alchemical combination of flawed vessels who, together, made something holy. Corgan brought the fire. Chamberlin brought the form. Iha brought the ether.

The music, the meaning, the Machina—is all three.

Psychology – Control, Legacy, and the Delusion of Sole Authorship

Billy Corgan’s artistic journey has always oscillated between messianic vision and monastic control—two poles magnetised by trauma, mistrust, and an almost sacramental belief in the sanctity of art. Few modern musicians have sought so forcefully to define the terms of their legacy. And fewer still have resisted so openly the dilution of meaning, the remixing of myth.

So when Corgan frames this reissue and tour as a completion of the Machina vision—a vision he claims was fractured by external failure—he is not being disingenuous. He is being honest. This is about redemption. Retrieval. Correction. It is the sealing of the scroll. But the scroll was never his alone.

The Romantic Author and the Seduction of Isolation

The cult of sole authorship—of the isolated genius—is not unique to Corgan. It was invented in the 19th century, as Romanticism eclipsed Enlightenment collectivity. Artists became prophets. Art became revelation. Genius was no longer a matter of training or tradition. It was bestowed. It possessed.

And with possession came isolation.

This is the tradition in which Corgan works. Like Wagner, like Blake, like Beethoven, he sees artistic output as cosmology—an emanation of a deeper order. His songs are not songs. They are transmissions. The band becomes the vessel. The audience, the congregation.

But the danger of this vision is its vulnerability. When misunderstood, it turns inward. When challenged, it hardens. When abandoned, it rewrites history. And that is what is happening here.

Winnicott: The Holding Environment and the Risk of Creativity

To create is to risk exposure. Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott wrote that true creativity requires a potential space—a secure environment in which the self can explore, experiment, and express without fear of annihilation. This is not about comfort. It is about containment. The infant has the mother. The artist has the group.

In this context, a band is not just a logistical unit. It is a holding environment. Jimmy Chamberlin’s return for Machina was not merely about percussion. It was psychological. His presence restored the conditions in which Corgan could safely explore a new sonic and narrative complexity. His drumming didn’t just anchor the music. It anchored the self.

James Iha played a similar role—not as co-author of the macro-narrative, perhaps, but as a tonal regulator, a relational mirror. His restraint, sarcasm, dissonance, and delay added spatiality to Corgan’s density. The Machine could breathe.

Without this holding environment, creativity becomes brittle. It becomes compensatory rather than collaborative. It feeds on control. And what results is not less beautiful—but less relational.

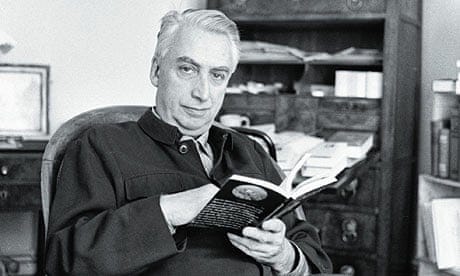

Barthes and the Fallacy of Control

In 1967, Roland Barthes declared the death of the author. His argument was not a denial of artistic intent, but a liberation of meaning. “A text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.” Once the work is public, the reader completes it. The artist may light the torch, but it is the audience that bears it forward.

Michel Foucault developed this further. In What Is an Author? he defined authorship not as essence, but as function—a social mechanism that limits interpretation. The author becomes a gatekeeper. A filter. A brand.

Corgan once rejected this role. The myth of Machina was fragmentary by design. Glass was not Billy. He was a distortion. A mirror cracked under the weight of prophecy. The audience was not passive. We decoded the lyrics, the bootlegs, the cryptic websites. We didn’t listen to Machina. We inhabited it.

Now, the gesture is reversed. Machina is to be restored. Finalised. Clarified. Not just sonically—but interpretively. The audience’s ambiguity is being replaced by the author’s correction.

This is not a problem of remastering. It is a problem of ownership.

The myth is no longer ours to unfold.

Berger and the Role of the Witness

John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, argued that perception is subjective. That art is never received in a vacuum. That we always bring our lives to the viewing. “We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.”

That is why Machina was sacred. Not because it was perfect—but because it demanded something of us. It asked us to look into it, not merely at it. And what we found—what I found—was not a band breaking down, but a cathedral breaking open.

When Machina II was released to a handful of fans and bootlegged online, it wasn’t an act of retreat. It was a gesture of radical trust. The band gave up control. And in doing so, gave us meaning.

We burned CDs. We mapped timelines. We downloaded low-bitrate MP3s of Home, Let Me Give the World to You, and the alternate Glass…. The audience didn’t just interpret Machina. We sustained it.

And now, in 2025, the myth has returned—but under lockdown. This time, we are not the stewards. We are the spectators, mere bystanders.

Authorship as Power—and the Tragedy of Fixing the Frame

None of this invalidates Corgan’s decision. He has every right to present his vision, especially given the pain of Machina’s original failure. The industry did fail him. The critics did diminish him. The audience was fragmented. This reissue is his vindication.

But it is also his severance.

Because to reframe Machina in large as a solo statement—performed under his name, with a new band—is not an act of healing. It is an act of containment. It is the very thing Machina warned against: the collapse of communion under the weight of singular voice. It says: “This is the meaning.”

And that is where the myth ends.

Because Machina was never about one meaning. It was about fractures, echoes, returns. It was about cracked voices harmonising despite themselves. Glass may have been the prophet. But the band—the Machines—were the church. And now they are gone and many fans are asking why…

The Justification That Doesn’t Hold – And the Led Zeppelin Principle

Billy Corgan has offered a rationale for touring under his own name. As he frames it, the Smashing Pumpkins name brings with it certain audience expectations—festival slots, big venues, and setlists dominated by hits. By stepping outside the brand, he suggests he can reclaim freedom: to play deeper cuts, to build something more theatrical, more cohesive, more in line with his current vision. It is, on the surface, a reasonable argument. Legacy is both weight and shadow. Corgan has never been one to meet the audience expectation head on - that’s what made the Pumpkins so real. So why hide behind the excuse, we can’t celebrate the deeper cuts, because it’s not what is expected of us. You can’t have your cake and eat it, as my Grandmother would say…

But the logic falls apart when you look at the content. This is not a tour of Ogilala, Cotillions, or TheFutureEmbrace. The show is built around three albums: Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, Machina (I & II), and Aghori Mhori Mai. These are Smashing Pumpkins records—spiritually, musically, and historically. They were not solo ventures. They were written, recorded, and mythologised with Jimmy Chamberlin and James Iha. To perform them now without that context is not merely a shift in branding. It is a redefinition of authorship.

The issue is not the songs. It is the ritual. It is the who.

You cannot celebrate a record born through reunion by removing the very forces that made reunion possible.

Consider the moment: the Bridge School Benefit, October 1999. Corgan and Iha take the stage alone at first—quiet, acoustic, reflective. Then, part-way through the set, Corgan introduces Jimmy Chamberlin. The band plays “Age of Innocence”— which would later become the last song on Machina. And after the final chord, Billy turns to Jimmy and says:

“You see, Jimmy… you are the difference.”

Billy knew it then.

The audience knew it.

We have always known it

We always will

(Skip to 17:40 to listen to the Age of Innocence)

So why the pivot now from Corgan?

One answer already came in Spring 1999, when the band launched The Arising! Tour. Small clubs. Raw shows (invoked by the press release). They played some unreleased formative Machina material live, as living myth, not yet fixed in tracklists or packaging. These were resurrection shows—new songs tested before loyal crowds, the chemistry restored. “Glass’ Theme,” “Wound,” “Heavy Metal Machine”—these weren’t just songs. They were signals. The Machine was running again.

This 2025 tour borrows or evokes the language and structural ambition of those shows. It is theatre. It is myth. But it’s hollow theatre. A re-enactment. The songs may be intact, but the spirit has left the frame. The magic is gone, not because the music is weak, but because the ritual of Machina is broken.

And that’s what makes the justification—that true fans wouldn’t accept a deep-cut Pumpkins tour—so utterly implausible.

The real, the true audience, The Ghost Children - those who would follow the band through thick and thin accepted and embraced The Arising! without question. They didn’t demand La Dolly Vita, Geek U.S.A or Muzzle - they were offered them as a gift, by the only drummer capable of doing them true justice. They are his parts and an extension his very essence… after all.

We, the fans, understood the Tour’s purpose, its limits, its significance. No one demanded the hits. In fact most of the talk in the fan communities was about the new songs. It was celebratory.

This new tour is none of the things the Arsing was.

Had Corgan simply named this “celebration” something like the Arising II - and explained what he hoped to achieve with a smaller set of shows, the audience of the Smashing Pumpkins would have completely understood. It would have been even more exciting… I think it would have been possible to “downsize” and play a smaller intimate tour than mega arena tours with Green Day. They could have done this. It wouldn’t have done the “brand” of SP any harm to bill a small intimate club tour for Machina deep cuts only… It’s a lazy excuse that doesn’t hold water.

Anyway re-framing context is not an error. But erasure is. This is not sentimentality. It is the musical truth.

And it brings us to a principle that many bands have understood, but few have honoured as clearly as Led Zeppelin. When John Bonham died, they ended. Because they knew he couldn’t be replaced. He was not a contributor. He was constitutive.

Corgan has often spoken of being misunderstood. Of carrying more vision than the industry or even his own bandmates could bear. That pain is real. But misunderstanding cannot become an excuse for selective recognition. If you wish your genius to be acknowledged, you must be willing to acknowledge those who carried it to completion.

You cannot demand recognition while withholding it.

You cannot mourn exclusion while practising it.

You cannot ask the world to honour the myth whilst undermining the foundations of reality.

This tour is perhaps not a complete betrayal, even if it feels like it to some. But it is a hell of a missed opportunity. A chance to reaffirm the myth by naming its authors. A chance to bring things full circle, not just in sound, but in presence.

Instead, the Machine appears without its operators. The sermon is delivered without the choir. It isn’t entirely wrong. But it isn’t whole.

When The Smashing Pumpkins become a setlist instead of a sacrament, something is lost.

When Machina is resurrected without its engineers, it becomes museum rather than memory.

Still, it’s important to say this clearly: this is not a “Siamese Zombie” complaint (as Billy might term this). I am not asking Billy Corgan to recreate the past exactly as it was. I am not wishing for that. I’m not asking him to do anything actually. I’m simply thinking out loud. As I have said, it is entirely at his discretion and I respect that - and you can be respectful and disagree at the same time. I am simply noting that there is an opportunity to “Return the Faith” and instead of faith in the band, The Smashing Pumpkins, he asks here instead for that faith to be placed in “Billy Corgan” instead…

Corgan or the bands desire to innovate is exactly why people love them and if anything, Machina was the moment the band made it crystal clear they would never recreate the past. The return of JC could have meant Siamese Dream 2, if they wanted to reclaim that ground. But instead, it was a rupture from grunge aesthetics and shoegaze nostalgia—a record that challenged form, burned bridges with critics, and tested its own internal mythology. It was the band’s most “sacred” record. And what made it sacred was not just the songs—it was the return of Chamberlin, the recalibration with Iha in a more leading role (taking up bass and guitar duties on many songs, in the absence of D’arcy), the sense that something had died and was being reborn, perhaps only to die again… But on it’s own terms. That mattered.

That risk, that rejection of expectation, was what defined the original Smashing Pumpkins. The irony is that it’s Oceania—a record made without Iha or Chamberlin—sounds more like “classic SP.” It’s well constructed, emotionally generous, even warmly familiar in parts. But to many of us, it felt like a cover band—a polished simulation of something once vital.

It’s in the subsequent records since 2018 —CYR, ATUM, Aghori Mhori Mai—where Corgan reclaims that discomfort. These albums are intentionally unrecognisable in parts: cold, electronic, metallic, longform, occasionally alienating. And while opinions vary, that boldness is in line with the Pumpkins’ lineage of experimentation. That’s why I have no doubt their legacy will endure in retrospect.

But that lineage was only reignited through the return of the full band. Jimmy and James’ presence legitimised the resurrection. They didn’t need to write every part; their presence alone re-established the frame. And in doing so, they re-enabled Corgan’s ability to take the band’s sound into bold new terrain. Without them, the story falters.

Of course, not everyone feels this rupture.

There are fans who simply trust Billy’s vision. On his private partly-paywalled Substack, there is only praise—unanimous support, shared excitement, and a genuine loyalty to whatever shape his art takes. Though that medium is again itself carefully curated and moderated to remove any detractors or any hint of disagreement with Corgan's narrative. Yet, the loyalty is valid for some. And I understand it, to a point. I don’t wish to mock or mute it. I don’t wish to tear Billy down or his fans. The man has given me—given us—decades of work that has shaped our imaginations and our lives.

But this is also why it hurts.

When music forms part of your emotional architecture, you don’t just consume it—you co-inhabit it. You stake part of your identity on the myth. And when that myth is reassembled without the people who made it feel real—without the chemistry, without the covenant—the spell, well, it is broken…

No artist owes us a performance or permanence.

But when something once felt so true, its reconstitution without proper context feels, at best, disorienting—and at worst, like mourning at a wedding.

You can’t please everyone. But The Smashing Pumpkins, at their best, were never trying to. Their greatness lay not in accommodation but in transformation—in becoming more than the sum of their parts, more than a band, more than even themselves. They were myth-making in motion, a collective act of becoming. The notion, then, that this Machina tour must proceed solely under the name Billy Corgan—as though the expectations of a Smashing Pumpkins audience could not bear the presence of its full spiritual lineage—is not just disappointing, in a way it’s devastating. It strikes at the very heart of what made them transcendent. If the mythology can only be re-enacted by suppressing its original forms, then what remains is not revival but reduction.

However, to be fair, Corgan’s caution isn’t without merit in one sense. It is true recent tours weighted toward hits have yielded stronger ticket sales and broader audience approval (or to the cynical) increased ticket sales—clear, quantifiable signals that familiarity sells. In that light, choosing to brand this tour under his own name could be read not as ego but as pragmatism: a safeguard against mismatched expectations. If you’re not going to play 1979, better to signal that up front, right? From that vantage, the decision makes a kind of strategic sense—protecting both legacy and live experience by ensuring the audience isn’t caught off guard.

And yet, it’s hard not to wonder whether this very tension—the refusal to capitulate, the insistence on steering against the wind—is itself the most Smashing Pumpkins move imaginable. After all, what is Machina if not a wilful act of defiance against commercial momentum? What is Glass and the Machines of God if not a myth constructed precisely to challenge, disorient, and reframe how we experience music and meaning? In that sense, maybe this tour is the right move. Maybe casting off the name, refusing nostalgia, and turning inward toward the obscurities and conceptual deep cuts is an act of integrity—not retreat.

But even so, one can’t help but feel there was a simpler option. Tell people the truth. Say it plainly: this is not a greatest hits tour. This is not 1994. This is something else, something rarer. Other bands do it—touring entire albums, B-sides, rarities, side projects. Fans follow, knowing what they’re getting into. It’s not beyond the wit of man to say: if you're coming for 1979 or “Rat in a Cage” sit this one out folks. If you're coming for the myth, for the machine, for the murk—step inside.

There was a way to make it work as The Smashing Pumpkins—by trusting that enough of us still care enough to follow the deeper thread.

And yet, when someone as intelligent and hyper-reflexive as Corgan describes this decision to go solo as “simple,” I’m afraid that rings entirely untrue against the history we know…

Conclusion – The Mourning of the Meaning

There is, undeniably, visible support on social media for the Machines of God tour. The surface narrative—amplified by press releases, images of theatrical lighting, and enthusiastic Substack posts—could on the surface suggest an audience thrilled to revisit Machina, Melon Collie, and Aghori Mhori Mai in a more intimate, conceptual frame. Among those most loyal to Billy Corgan’s evolving vision, there is trust. They hear new music and are grateful. They see his effort and appreciate it. And they are right to. This project has clearly meant a great deal to him, and that should never be dismissed. I am envious that they have joy without question. You support a football team whether or not they are winning or loosing. I get that. But most fans don’t mind saying, I still love you, but that last game was a shocker mate… and they should be able to say this without their season ticket getting revoked.

However, underneath that surface is something more complicated. Beneath the celebratory likes lie questions. In the shadows of approval, confusion lingers. Scroll through the Instagram announcement’s comment thread—beneath the emojis and “Can’t wait!” messages—and a different tone emerges: Why isn’t this a Pumpkins tour? Why aren’t Jimmy and James involved? Why is this being done alone?

The most liked comment on the band’s official Instagram page (their biggest social media platform), with over 248 likes, says simply:

“Why do this? The Pumpkins are an active band.”

Others follow suit…

At the time of writing, around 20% of comments engage with this sentiment directly, but they absolutely dominate in engagement. This is shared and true across social media including X and the fan forums, such as Netphoria.

It is identity, not nostalgia, that animates the fans. They’re not asking for Siamese Dream 2 —they’re asking who gets to hold the myth now?

That question is not hostile. It is a plea for coherence. The meaning of the Arising Tour was obvious. My initial reaction to this, as with many others, was disbelief and total confusion. How can you truly celebrate Machina, without those who made it?

But Corgan, like as (?) Glass, has every right to position himself in isolation or with different Machines. However, in doing so, he can not also expect fans to stay loyal to albums or ideas when he can casually try and re-author the meaning like this. A “simple” decision to go alone. I think not. And expecting us to believe this after careful curation of 30 years of music across multiple avatars and iterations - I'm afraid nothing has ever been just “simple”. Corgan says he’s started and abandoned various drafts of his own autobiography over the years. I can’t pertain to know the exact reason behind this, and in some way’s it’s strange to speculate - but given the tangled and messy history and inconsistencies over the years, I am sure, a bit like with Machina, bringing order to Chaos, to control, where there is none is no mean feat.

I thought he wanted a discerning audience, but perhaps I see now, he just wants loyalty.

Some would say this is now typical of Billy Corgan or his prerogative.

He builds, he destroys, he reframes, he asserts control. The mythology of the misunderstood genius is one he has shaped carefully over the years. And much of it is true. He has been misunderstood. He has taken real artistic risks. He has refused to be reduced to his own early success. But what’s happening here isn’t just another artistic pivot. It’s something stranger: a resurrection without a body. A celebration of reunion, performed alone.

And that’s where the dissonance begins, but doesn’t resolve…

Corgan has said publicly that he’d be fine with his children carrying on the Smashing Pumpkins name after he’s gone. This is not to him then a scared band, then. Where unique musical identity matters. Where individuality is celebrated.

This is now a venture. A legacy vehicle.

It is not inherently wrong to imagine your work continuing in your absence—but that model only truely really works when the brand was abstracted to begin with. Slipknot created a rotating mythology that allowed members to become symbols. The Residents, Gorillaz, even King Gizzard—these are brands, or systems. That said - maybe Billy consider’s a holographic version of the band like Abba as a legacy he’s happy with…?

But to me, anyway, The Smashing Pumpkins were not a system. They were four people.

Billy, D’arcy. James and Jimmy: Zero and The Smashing Pumpkins, Glass and The Machines.

That was the fact, not the myth.

We knew their faces. We knew their instruments. We knew their failures. This was not an anonymous collective. This was a symbiotic relationship.

And relationships are sacred. They cannot be rebranded. You can not expect the rest of the world to respect the legacy, if you no longer do…

This is perhaps the crux of the issue for me (and others). Billy wants the band (The Smashing Pumpkins) to be recognised as significant. As canonical. And he is right—they should be. But reverence is not self-generated. You cannot insist on respect while deconstructing the very reasons it existed and was important. You cannot create a sense of legacy while stripping out the people and dynamics that forged it. You cannot ask us to believe that this work is still sacred, and then reconfigure it in a way that breaks the very alchemy that made it sacred in the first place.

I say this with humility: I know I don’t matter. I’m one of many. A listener. A drummer. A fan. A witness. I have no special insight into the internal dynamics of the band. I don't speak for anyone or believe the band or Billy Corgan owes me or anyone else anything. This myth, as I see it, is personal and I know to the vast majority of people - I may sound slightly unhinged in writing all this about a band… it's just music, it's just songs…